Was a Newspaper Strike a Bigger Villain Than Bucky Bleepin’ Dent in 1978?

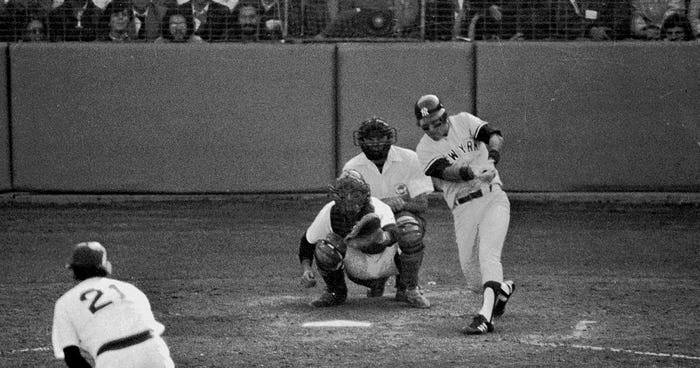

Could one of the most painful games in Red Sox history — the Bucky Bleepin’ Dent one-game playoff loss in 1978 — have been avoided if New York City newspapers hadn’t gone on strike that summer?

That thought had never occurred to me, until I watched “14 Back” — Jonathan Hock’s brilliant documentary on the ’78 season for SIFilms [https://si.tv/movie/14-back-1402] and read SI author Tom Verducci’s contemplation last month [https://www.si.com/mlb/2018/09/20/14-back-documentary-yankees-red-sox-1978-pennant-race] of the Yankees’ rally from 14 games behind the Sox on July 19th to their 5–4 win in Fenway Park on Oct. 2, 1978, 40 years ago today.

For much of that spring and summer, the Yankees’ clubhouse had been riven by the daily soap operas revolving around the toxic relationships among owner George Steinbrenner, manager Billy Martin, slugger Reggie Jackson and team captain Thurman Munson, with other chracters cycling in and out of the melodramas. The avaricious New York press served as chronicler, framer and often instigator of the intramural conflicts that generated almost constant headlines, the Yankees barely staying above .500 while they languished in fourth place, far behind the supremely confident Red Sox. Martin resigned/was fired, Jackson was suspended, and Steinbrenner regularly injected himself into the chaos, while the Yankees slipped farther and farther behind.

While the Yankees had sliced a half-dozen games off the Sox lead by early August, team PR man Mickey Morabito on Aug. 8 arranged a lunch for the beat writers with exiled manager Martin. To Morabito’s horror, Martin unloaded again on Jackson, whom he had lumped with Steinbrenner in one of the baseball’s most memorable damning quotes (“One’s a born liar. The other’s convicted”).

“I never looked at Reggie as a superstar,” Martin was now saying. “He never showed me he was a superstar. I never put him over Chris Chambliss or Thurman Munson or Willie Randolph or Mickey Rivers. There were times I put Chicken Stanley ahead of him.’’

“Chicken Stanley” was light-hitting infielder Fred Stanley. The writers had barely placed their napkins on the table before they were on the phone to Steinbrenner. Morabito, now the traveling secretary for the Athletics, assumed he was a goner.

Except: There were no headlines in New York the next morning. The pressmen for the New York Times and the city’s two tabloids, the Daily News and Post, had gone on strike. Morabito’s job was safe. More importantly for the Yankees, they were now allowed to operate in relative obscurity for the balance of the season.

“That’s the thing that helped us immensely,’’ Yankees outfielder Lou Piniella said, “the newspapers going on strike. That gave us the rest and reprieve we were totally looking for.’’

Third baseman Graig Nettles agreed. “That was a lot of fun, not having those guys (reporters) in our face. A lot of ’em were there just to stir up (stuff). For two months, we didn’t have to worry about what angle was being portrayed about us. It was great.’’

Bob Lemon had replaced the hard-drinking, volatile Martin as manager. Lemon liked his libations, too, but was more low-key about it.

“The strike, coming when it did,’’ Lemon said, “did more for us than if we picked up a 20-game winner.’’

The Yankees were in third place, 8 ½ games behind the Red Sox, when the strike began. They went 38–14 the rest of the season.

The Sox, meanwhile, were regularly reading what chokers they were, especially after the infamous ”Boston Massacre,” when the Yankees swept four from the Sox in Fenway Park by a combined score of 42–9, the Sox committing a ghastly seven errors in the second game, a 13–2 loss.

The “choker” appellation didn’t stick after the Sox, who had fallen 3 ½ games behind the Yankees, won their last eight games to force the playoff. That game, though won by the Yankees, 5–4, remains one of the greatest games ever played, one that did not end until the great Yaz, facing Yankee closer Goose Gossage with the tying run 90 feet away, popped out to Nettles. Before that at-bat, closer Gossage said in the film, “I was shaking so bad, my body was just trembling.’’

Forty years later, Fred Lynn said, the memory still aches.

“I’ve come to grips with it,’’ he says in the film, “but it gnaws at me. It wakes me up. And I’m 66 years old.’’